20 July 2012

It also seems that the majority of those blessed with genius are liable to be cursed, in the gentlest way, with a streak of naivety - which is often endearing, but can also be mistaken for lack of judgement. To a ten year-old mind, this naivety was as familiar as my own innocence, and was instantly embraced, but to a seventeen year-old, who by then had experienced the cynicism of others, and who loved his grand-uncle, it became something from which he had to be protected.

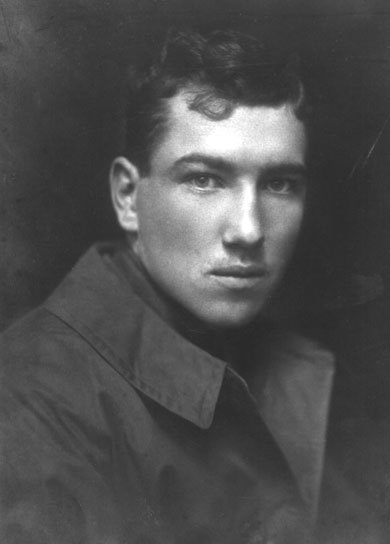

Our author, Simon Gough talks about The White Goddess: An Encounter, the writing life and the inspiration he received from his famous relative, Robert Graves.

What can you tell us about Robert Graves?

Robert was huge, in every way - 6' 2" tall, and built like a prize-fighter, with a badly broken nose (from boxing at Charterhouse and in the army), and yet a nose which could just as well pass, given his 'bringings-up' and his bearing, for a Roman nobleman's. His character was equally at home in both worlds : he could be as urbane as Augustus Caesar, and yet knock someone flat with a single blow - which happened on more than one occasion.

Although we'd first been introduced when I was in my pram and been dutifully kissed and patted on the head in direct line to Queen Anne (as he rather quaintly insisted - see 'Goodbye To All That'), I didn't truly meet him until 1953, when I was 10, when my parents - both actors - were in the middle of a messy and very public divorce. (In those days divorces were less common than now, and a very public matter, particularly in the theatre, with everyone taking sides). My mother, Diana Graves, who had a long history of T.B., became ill, and was rescued (not for the first time), by her uncle Robert, who sent her enough money to fly out to Deya for a proper holiday in the sun (which she hated) to be followed by me when my school term ended that July. So my mother went on ahead for a month or so - spent mostly in bed - where she was given a sympathetic talking to by her uncle, and aunt Beryl, while I counted the days to real freedom, and my first trip 'abroad'.

From the moment I stepped off the 'plane into the crushing heat of Palma in midsummer, my grand-uncle (as he insisted on being called - "Great is for steam-ships and railway lines, don't you think? Grand is for fathers and uncles - and Russian dukes, of course - !"), he and my great-aunt Beryl seemed to know instinctively everything I wanted to do or say, even before I did myself. This second sight, on Robert's part, lasted through my childhood and youth, only deserting him when his anxieties about his Muse became all-consuming. Having convinced himself that the The White Goddess was putting him to the hardest test of his life, he seemed to withdraw into himself, perhaps to consolidate all his powers for what he foresaw as the terrible battle ahead. This loss of insight was to have disastrous consequences for almost everyone.

What impression did he make on you, and on others?

As I say, he was larger than life in every way. To a 10 year-old he was like an ancient Greek God, all-seeing, able to forecast and foretell, and to 'see through one' at the drop of a hat. He was surrounded by magical objects, from mushrooms to mystical charms from ancient Egypt, Greece, and Africa, many of them given to him by archaeologists like Max Mallowan, and other explorers and anthropologists who admired him - as did most unconventional people, because there was almost no subject they brought up which he didn't know something about (sometimes rather more than the 'expert' who had brought the subject up in the first place). Also, his knowledge of obscure subjects was phenomenal, as was his capacity for work. At one point, in the '50's, his published output was second only to Agatha Christie's who, so far as I remember, held the record for the number of books published in English at that time. The difference between them, of course, was that her output was mostly confined to detective fiction, while his embraced the whole gamut of literature.

His brain moved so quickly that some of his critics accused him of slapdash work, or of leap-frogging facts he disagreed with and bending the truth to his own view of it, and yet his instincts were often proved right in the end. He generally worked from sunrise until late into the night, with breaks only for meals, when he told anyone who happened to be at table what he'd accomplished that day (which was occasionally mistaken for boastfulness), and for his daily bathe - a long, bracing walk of over a thousand feet from the house down to the beach (the cala), or to a beautiful secluded jetty at Lluch Alcari, guarded by a locked gate, which was further away, but a place where he could either be alone, or talk privately with whomever he'd chosen to walk with him that day.

When I returned to Deya in 1959, on my way to university in Madrid, he'd drag me off with him to bathe if there was no one more interesting around, because on the whole he preferred company. As I grew closer and closer to his muse, Margot Callas, he'd seek out my company more often, since she was not only his favourite topic of conversation, but I was as hungry for information about her as he was desperate to share it. There were also long periods when his children, my cousins, were at school or university in England and Switzerland, and only Beryl and I were in the house to keep him company. Although she liked Margot enormously, Beryl was more than a little relieved when Robert unloaded his constant anxieties about her onto someone else for a change. As I describe in the book, 'The White Goddess : An Encounter', these conversations with anyone who'd listen to him grew more and more distraught and paranoid as his desperation about Margot increased… Not paranoid in the psychotic sense, but in the way that people in love, when they know something is seriously wrong, turn every stone in their search for reasons - and for omens in his case. The horror, for me, was that by then this was the one subject on earth which I knew more about than he did, and yet I'd been sworn to silence on pain of death.

His loyalty and generosity to his 'true' friends (as he called them), was remarkable and enduring, provided that he was never deceived or cheated by them. In return, this huge inner circle defended him and his reputation to the hilt. It seems to be in the nature of genius that the more controversial you are, the more vociferous and impassioned your supporters become. It also seems that the majority of those blessed with genius are liable to be cursed, in the gentlest way, with a streak of naivety - which is often endearing, but can also be mistaken for lack of judgement. To a ten year-old mind, this naivety was as familiar as my own innocence, and was instantly embraced, but to a seventeen year-old, who by then had experienced the cynicism of others, and who loved his grand-uncle, it became something from which he had to be protected. Beryl, as his truest champion of all, set the example for everyone else, discreetly watching his every step and warning him of pitfalls and dangers.

Another problem with his unwordliness was that it made him more susceptible to flattery - and to criticism - both of which had to be guarded against. Occasionally he was taken in by con-men or bounders, notably by a financial consultant in Switzerland who looked after both him and Graham Greene, and vanished with both their money. As for criticism, a bad or over-critical review (a memorable one by John Wain, I recall), could lay him low for weeks.

Central to 'The White Goddess : An Encounter', is your great-uncle's notion of The Muse, the effect it had on his life (as well as the lives of those around him), and the effect it had on you. How did his belief strike you? Do you subscribe to it?

When Robert first wrote 'The Roebuck in the Thicket (the precursor to The White Goddess), in 1944, I wasn't yet two years old, and knew nothing about it. When he first inscribed, and then chucked the newly-arrived Faber paperback edition at me across his desk at Canellun on April 9th, 1961 (the date had to be changed in my book), I still had no idea what the book was about, and asked him if it was a novel. Fifty years on, and I'm still not much the wiser - nor wish to be. Robert's rarified scholarship, the manic pace of his brain, which forced him to take endless shortcuts in his prose (where he expected his readers to follow him blindly down whichever path he chose to take them), and his mother-inspired obsession with Christianity were all either too scholarly, too incomprehensible, or too unacceptable for me to follow. What I believed in then (and still believe, without the slightest doubt) is that Margot was the earthly incarnation of The White Goddess. She, and she alone, inspired his greatest lyric poetry, and her inspiration overflowed into others, then and now. I no longer have the time to worry about cryptic alphabets, The Battle of the Trees, The Roebuck in the Thicket, or the origin of the Cult of the White Goddess on the shores of the Black Sea (unless such enlightenment should suddenly epiphanise before me in the next year or so). I am simply and profoundly grateful that I can write at all, in whatever form, and have dedicated the rest of my life to that simple precept, in gratitude to a deity whom I will recognise at once if she should ever appear to me again in mortal form.

How important was Beryl Graves to Robert, to her immediate family, and to you?

No recollection of Robert could ever be complete without an instant and equal evocation of his extraordinary second wife, Beryl. My first great-aunt, who was very eccentric, and whom I therefore rather liked, was Nancy Nicholson, daughter of the artist William Nicholson, and sister of an equally eccentric painter, Ben Nicholson - whom many people found 'difficult', but who was always very kind to me (I think he had a soft spot for lonely children, and encouraged me to paint - very badly). As a child, I thought one only ever had one great-aunt for every great-uncle, but in Robert's case I was spoilt for choice. What was even nicer was that they were so different that one could love them both in completely different ways, without feeling disloyal to either.

Beryl was a phenomenal woman, and (I had to secretly admit to myself) the best great-aunt (and mother), that anyone could wish for - calm, caring, compassionate, and everything wonderful that began with any letter of the alphabet. As far as she was concerned, children and animals came first, before even Robert, so for a boy of ten it was like having a fairy godmother whom not even my own mother could overrule.

Having distinguished herself at Oxford, Beryl was more than intelligent - she also had an instinct that was second to none, on which Robert relied more and more; she never had an axe to grind, and almost never said an unkind word about anyone unless they'd cheated Robert or her children in some way. Her laconic judgements and decisions were brief and quietly spoken, and yet whenever her opinion was asked for, the room always fell silent until she'd had her say.

The Gordian knots of Robert's emotions or problems were invariably sliced through with a perspicacity as sharp as Solomon's. She was the foundation-stone of his life from the moment they fell in love in the late 1930's, a love which provided desperately-needed calmness and stability to a man who had become frazzled by his relationship with his fist muse, Laura Riding. Together with Robert's secretary, Karl, Beryl quietly and unobtrusively reorganised Robert's life so that he was as free as possible to get on with his ever-increasing workload - and his poems - without the distraction of endless chores and time-wasting correspondence which threatened to inundate him. It is my personal belief that she not only fell in love with him, but with his poetry, as if they were two quite separate entities of Robert's personality, the first part, however maddening and chaotic sometimes, almost touchingly human, the second, his poems, not far short of divine in their depth and clarity. In the later years, she set herself the huge task of organising and editing his thousands of poems with Dunstan Ward for the definitive edition of Robert's complete works, published by Carcanet in 21 volumes.

A section of the book is set in Madrid during Franco's dictatorship. You describe the city as a hard, cruel place. How did you manage to survive living there after being brought up (in school holidays at least) in Rome and Italy?

The difference between living in Madrid and living in Rome in the early 1960's was (I can only imagine), like living first in West Berlin and then in East Berlin before the Wall came down. I came to believe that the reason why so many 'civilised' countries thrive under dictatorships is that they concentrate and polarise the mind wonderfully; the 'masses' are safe in the reassurance that they know precisely where they are and what the punishments are for being anywhere else, while the agitators and the 'intelligentsia' know precisely where they are, resent it even as they thrive intellectually under repression, and end up either dead, in prison, or in exile. So far as the Spanish police were concerned, I was merely a young foreigner attending university there, with rather more money in my pocket than many Madrillenos. While such money as I had was welcome in Spain, my beliefs and opinions were not.

In terms of sheer beauty, history, art and architecture, there was no comparison at all. While Rome was ravishingly beautiful and endlessly fascinating in the 1950s, Madrid was architecturally barren apart from its Old Quarter, dirty, stinking, and peopled by beggars who had mostly chosen the wrong side in the civil war which had ended only twenty years before. The squalor in the older parts of the city was almost indescribable - although I've done my best to recreate it faithfully in the book. In winter the buildings literally creaked in the iron grip of snow and ice - a grip which could be compared with the grip that El Caudillo' (Franco) held over the population, while in the height of summer the relentless heat and stench of the city was overpowering, with the smell of raw sewage seeping like brutal reality out of iron gratings in the streets and gutters. The inhabitants, on the other hand, more than made up for the dreariness of the (relatively modern) capital by being individuals down to the last man, woman and child, deeply proud of their existence, as capable of great violence of feeling as they were capable of great kindness.

Madrid's one huge advantage over all other cities in the west was its almost unbelievable cheapness; one could eat well for a shilling (5p today), cross the city in a taxi for a shilling, and even buy a new shirt for a shilling. Although there were a number of wealthy Spaniards - like the banker Juan March - and a middle class set in the aspic of its own past, the poor, who far outnumbered everyone, were kept almost ruthlessly poor; the more distracted they were by the endless grindstone of having to live hand-to-mouth, the less chance there was of their looking up from their miserable lot and rebelling. Fear was the key, and Franco a supremely efficient locksmith.

My mentor in Madrid was the journalist, writer and poet, Alastair Reid, a close friend of my mother and of Robert's, who was politically as canny as the Scot that he was, and clever enough, in the way he phrased what he wrote, to slip under the radar of many a censor. In those days, journalists had no second chance; if they stepped out of line they were deported - if they were lucky. Living in Madrid with a wife and child made him even more vulnerable, but luckily for him, Franco had begun to realise that Spain could no longer go forward in isolation, either politically or financially, but needed the support of the outside world. The growing success of tourism, in the Balearic Islands in particular, had caught his eye, and he wanted to make more of Spain attractive to foreign currency and speculators. For that reason, a slow thaw in his attitude to foreign journalists allowed Alastair more leeway than many of his predecessors had enjoyed, and he made the most of it - very cleverly. He was a survivor in the truest sense, and therefore, as Robert called him, a 'loner'.

Where have you been all your life, and what inspired you to write 'The White Godess: An Encounter'? Have you always written?

When I was first diagnosed with Lymphoma in 1988 and graciously given five years to live, I took the Professor at his word and brought about a sea-change in my life. At the time, I was an antiquarian bookseller with a shop in Holt, in Norfolk, and second shop, Food for Thought, (which specialised in books on food and wine), in Cecil Court, off St. Martin's Lane in London. However, I had 'scribbled' since I could first fill a fountain-pen - school plays, then scraps for The Young Elizabethan, whose editor, Kaye Webb, was a family friend, then poems (never offered - quite rightly - for publication), and finally broadcasts for the BBC, commissioned by other family friends. Where would we be without nepotism? More successful, is probably the true answer, but in those days, and in the years between 1952 and 1976, when I sporadically followed my parents, cousins, and god-parents into the theatre, it was easier to find work than to turn it down. My only attempt at cutting the umbilical cord and actually look for work was when I was thrown out of school at 15 and ended up at The Manchester Guardian, where I finally became sub-secretary to Gerard Fay, the London editor. But even there, my mother asked Robert to write me a reference, which probably got me the job anyway.

The monkey on my back, however, had always been writing, and like the devil it was, I hated it as much as I revelled in the few moments when I actually got something 'right'. Poetry was a whole other nightmare altogether - the most dementing of all disciplines. Only someone as inhuman and devious as a Goddess of her own Mysteries could have inspired men and women to alchemize prose into songs, songs into verse, and verse into poetry itself - something as near perfection as the silence-of-mind that gives birth to it.

After the diagnosis, I was determined to somehow run to earth the cause and reason for this illness, with my pen as my only means of attack or defence. In the belief that I could somehow create my way back into a second life (or a second chance, at least), I began to write - and fight - my way back into the past, which finally brought me to one event in particular, which I'd buried so deeply that I never imagined I'd ever stumble over its grave again. To most people nowadays, it's probably nothing more than 'just another story' - which I suppose it is - and yet to me at the time it was my story - a love story, and a true love story at that. It was also a story of betrayal and revenge, which hurt so much to recall that I realised that what I'd mistaken for a corpse, and buried so deeply, was in fact still living, and had been buried alive.

So, in 1989 I told this part of my story to a close friend, Johnny Byrne, who had written for 'Doctor Who', created the television series 'All Creatures Great and Small', and 'Heartbeat', and so on. He found the story gripping enough to ring his Script Editor at the BBC, Joy Layle, and asked her to come up to Norfolk for the weekend and hear it for herself. She turned out to be the most extraordinary, charismatic woman, with an ear (and a camera's eye) for a good story that was second to none. Once she'd heard mine, she asked Mark Shivas, who was then Commissioning Editor at the BBC, to commission a synopsis, which he then followed with a commission for a three-part television series for BBC 2, on condition that I received no money until each episode was 'signed off' by its producer, Michael Wearing, ('The History Man', 'Boys from the Black Stuff', 'Edge of Darkness'), because no one knew if I could actually write. The series went into pre-production at the very moment when the El Dorado fiasco blew up, and New Brooms were sent for in panic to clear out the Old Guard at the BBC, with catastrophic consequences for its reputation as producers of original and award-winning drama. As for any production that was to be shot in Spain, they were automatically axed - and a saving of £3.8 million on The White Goddess was, according to Joy, a fine and meaningful trophy for the New Brooms to wave at the Director General.

How long did it take you to write The White Goddess: An Encounter? Can you describe your writing day? What are your personal thoughts on writing?

Rather than go into a decline after the television series was dropped, I decided to do what I'd intended to do in the first place, and write the story as a book, though not as a Me- Me- Me-moir, as P-P-Paddy Campbell might have described it, (since who on earth would want to read the autobiography of a complete nonentity), but as a simple narrative, told as far as possible in the instantanaeity of its happening.

I started the book in 1996, some years after my first death sentence had expired, when I rented a small barn in the village to escape all distractions between 12.30 and 7pm every day. After supper, and when my wife had decided she'd had enough of me and gone to bed, I'd transfer whatever I'd written during the day onto a computer and start editing it until 2 or 3 in the morning.

The book became enormous, as you can imagine after thirteen years, but that didn't bother me particularly; no one had commissioned it - I wasn't writing for anyone but my wife, my children and myself, and my children could wait. It was only when 'needs musted', as Robert used to say, and the wolf was actually smashing the door down, that it was decided to try finding a publisher. Or an agent. Or an editor - or something faintly useful, even though I was far from convinced that it was ready. So I sent bits of it off to an agent and a couple of publishers, and went back to work. The agent's reaction was interested (the publishers, predictably, weren't), but I ended up in the hands of a remarkable editor, Mary Sandys, who suggested that I split the book into four, making each book far more manageable.

'The White Goddess: An Encounter' is the third of the four books, with a sequel already half written, and with two precursors awaiting a final edit before they, too, are put to bed until judgement day.

Having been brought up among the weirdest mixture of artists, writers and poets - from the drunkest to the most totally-teetered, from the most despised to the most respected - I've always been fascinated by their work habits, by their 'tics' and superstitions - and by how their 'other halves' have coped with their often almost impossible demands. On the whole, the writers I've known have seemed either to work for a certain number of hours - most often from early in the morning until lunchtime, when their minds were at their clearest (and sometimes, if things were going well, from lunchtime until tea); or they'd wait until their hangovers had cleared and write through the afternoon and into the evening, or their goal was to write so many words a day, regardless of the quality or of how long it took, knowing that everything would be sorted out later, in the editing, or they've used a combination of disciplines. Some regarded their work as nothing more than 'a 9-to-5 job', others were 'inspired' up to a point, and yet could put down their pen in mid-sentence when the clock struck one, while others didn't even bother to pick up their pen at all unless and until a whole sentence was perfectly formed in their heads.

No matter how hard I tried, I never quite managed to fit any of these templates. I wrote because I couldn't do anything else creatively, and because I kept being given 'dead'lines by quite extraordinarily inaccurate professors or doctors of oncology who eventually retired, or kicked the bucket themselves. In all humility, and with all my heart, I believe that it's possible to transcend anything, even death, with inspiration, creation and fantasy.

Once I pick up a pen, I don't put it down until I've achieved something, however mere - something which is at least as close to the truth of what I'm trying to say as I can possibly get at that moment. To be able to express oneself at all is an incredible gift, a gift not to be ignored or rationed or wasted. As a writer, you either write until you've run out of ink or paper or he means to write in any other way, or you write until you drop, or you write until you drop dead.

What made you feel that the book was 'ready' after so long?

Henry Layte, owner of 'The Book Hive', and one of the directors of the Galley Beggar Press, decided that it was, although in fact the book was far from ready. Henry had virtually been brought up with the story because I used to read parts of the books to his parents - at their insistence, I hasten to add - and copies of it used to lie around the house from when Henry was a mind-bogglingly barking teenager, driven by demons as wild as his imagination. Early last year he and Eloise Millar and Sam Jordison decided to found The Galley Beggar Press, and Henry proposed 'The White Goddess: An Encounter' as their first title. To everyone's astonishment, they all agreed, subject to editing. I've had a number of editors in my life - usually very bright women, like Jean Metcalfe, Joy Layle and Mary Sandys. To have one editor is a great luxury - to have three at once is a nightmare - like being locked in the suite of a six-star hotel in Portofino with the doors and shutters locked from the outside, with nothing but 350 pages of manuscript to eat, drink and sleep on - and page after page of suggested corrections vomiting out of a printer in another room. I should have been so lucky.

Although every word of the book is mine, it's not the book I first wrote - but that's something you have to get used to if you have an editor you respect. If you have three editors… What I particularly liked about them, though, was that they were democratic: if two of us proposed a cut and two were against it, the pair which included me was given the benefit of the doubt - for that day, at least. What was even luckier was that they were all intelligent, and one of them was even very pretty. Aesthetics are terribly seductive - even more so when you're seventy. As far as this book is concerned, I owe them all everything. Hopefully, we'll all be quits one day.

The village of Deya in Mallorca, where most of the book is set, seems hugely important to you. What was it like when you first went there in 1953, and when you returned in 1960? What is your relationship with the village now?

I was incredibly fortunate, in my boyhood and youth - and as a young man - to have spent so much time in so many 'earthly paradises'. Robert's daughter, Jenny Nicholson - my 'sweetest coz', as we called each other - lived in a tower in the middle of Trajan's Forum in Rome and owned the most magical fairy castle called the Castelletto, on the highest point of the farthest hill above the sea overlooking Portofino. From there we'd visit every mountainous seaside village on every island from Elba to Ischia, yet never found anywhere quite as unique, for the drama of its setting and for the harsh beauty of its landscape, as Deya. Its precipitous landscape, flling over 4000 feet from the Teix mountain above the village, to the cala, is matched only by the depths and dangers into which people can fall if they aren't careful. Those it dislikes, or have no business to be there, it it simply spits out, either by causing them to suddenly 'vanish' as if they'd never existed, or by killing them.

A few years ago, as a guest of my son-in-law's at a most exclusive hotel there, I had breakfast next to a couple of middle-aged Americans. When I asked if they were enjoying themselves in Deya, the man was amiable enough, but his wife, dripping in diamonds at nine o'clock in the morning, couldn't contain her dislike for the place, for its primitive people, plumbing, paths, poets, painters and panoramas. The one word she rather foolishly left out was 'premonitions', because by lunchtime she was dead, having tripped on a stone step on the path back to her room and split her head open on the rocks.

The spirit of Deya, and of the whole mountainous north coast of the island, is as alive and watchful today as it has always been. Even when I was a boy, being introduced to its dangers by my wild nine year-old cousin Juan, I was aware at once of the strangeness of the place, of the mischief it could bring about if it took against you, and of its tendency to cause life-quakes among the people who lived there. There was also no doubt in my mind that the epicentre of these sometimes cataclysmic disturbances was Canellun, the house which Robert and Laura Riding had built just outside the village in the early '30's. And yet not even Laura was immune to the watchful forces of Deya : when she spent a fortune - of Robert's - building a road from the house down to the cala (the beach), and then attempted to sell-off building plots along its length, the road was washed away. One day the same thing will happen to the houses which have recently been built, of ugly black rock rather than the native sandstone, overlooking the cala.

When I first went to Deya in 1953, there was only a handful of foreigners to the 500 or so native Deyans. Nowadays, in the height of summer, the foreigners can be counted in their thousands, while the native population has only increased in proportion to the jobs available in the hotels and restaurants which cater for the tourists.

As for the beauty of Deya, the enduring affection I feel for its people, and the abiding spirit of the place, I had to write a 600-page book, 'The White Goddess : An Encounter', to even begin to describe what it is truly like. My cousin, William Graves had the same problem, which he finally managed to express in his moving autobiography 'Wild Olives,. as did Lucia and Tomàs Graves in their own accounts of the village, and of their lives there - all well worth reading.

What are you working on now?

For the last year I've been revising - and trying to finish - the quartet 'The Flight of Icarus' which I first started writing in 1996. 'The White Goddess: An Encounter' is the third of the four books, the last book being the sequel to it.

Whenever we go abroad - usually to a tiny fishing village in Portugal which we've grown to love - I take poems with me; they're much lighter - in weight, at least - and seem to inspire new ones. So while my wife swims and lies in the sun with our friends on a nearby island, I sit in the shade outside cafés and work until lunchtime, when I take a ferry across to the island and have unforgettable picnics with them. At four o'clock I return to the shore and continue working until they've all had enough, grab the last ferry, and join me.

Comments

Thrilling

Permalink Submitted by Monroe Holmstrom on 23 August 2012.

This book is thrilling and excieting you should so buy it and read it you will be on the edge of your seat and reading very quickly so you can know what happens.

Great!

Permalink Submitted by Domonique Esten on 23 August 2012.

This book is great. Well written and just great.

Dear Simon

Permalink Submitted by Graeme Fife on 8 September 2012.

Dear Simon

Perhaps you don’t remember me, but I brought Lucia and Ramón to your house, once, bought a secondhand edition of Ency Brit from you and sold you a pristine dust sheet of The White Goddess.

I’ve just finished your book – knowing all the people in it drew me, of course. I applaud the feat (agonising, it feels) of recollection and record.

Perhaps you don’t know that the wonderful theatre in the olive grove which you built (which Ronnie Wathen called The Graves Armpit Theatre) was one of the venues a small company of professional actors and I with local amateur support used for a Week of Plays in Deia in 1984. Eight performances, five productions, plus street theatre, in seven days, concluding with The Tempest in that magical setting. On the morning of the last performance, I went down to see Jakov in the Mirador and sat on his terrace as we watched a real tempest marching across the sea towards the Cala. It hit with astounding fury and we drove up into town, in his old Fiat 500, weaving up the track through blasts of gale and pelting rain to find water running a foot deep in the gutters. At lunch, in Jaime’s, Tana Waldren was saying that when it rained like this it was set for three days. Lunch done, I said Well, I am going to bed and woke at four o’clock to bright sunshine. Our Tempest had, it seems, seen off the storm. And when the play was done – months before, that Easter, Beryl had bid me Find out moonshine to fix our dates – our Ariel, played by a wonderful street clown of surpassing grace and twinkle, took her lantern up into Robert’s room to say some of her speeches to him.

I hope the book sells – it deserves to.

Best wishes

Graeme Fife

I loved your book

Permalink Submitted by Robert Dudley on 28 May 2013.

I loved your book. I think we are probably about the same age, but I admired enormously your ability to write in a way that seemed to me authentic about the intensity of teenage love. A completely immersing and enchanting read. Thank you very much.

I have always remembered hearing your great uncle lecture at Oxford and him saying that as a boy (I'm pretty sure this is what he said) he'd had an experience of omniscience – he was aware that there was nothing about the universe that he didn't know and understand. I think he said it lasted for some days. How wonderful for you to have had the sort of intimacy you describe so vividly with him.

Add new comment